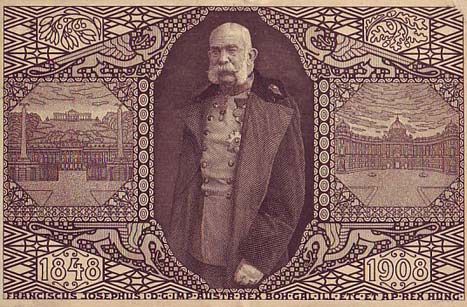

Emperor Franz Joseph I

Like Britain's Queen Victoria, whose reign lasted sixty-four summers, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria became an unshakeable symbol of his era. The mutton-chop whiskered monarch managed a whopping sixty-eight years on the Habsburg throne, becoming a much-loved figure throughout the Empire. He liked well-polished shoes, boiled beef and he never missed a chance to chase a fox or shoot a stag. On the minus side, the Emperor wasn't so keen on telephones, elevators or flushing lavatories - newfangled gimmicks that weren't to be trusted. Dutiful and hard-working, he got up well before the crack of dawn, and carried out his manifold duties with dignified aplomb. And unlike Queen Victoria, who largely retreated from public life after the premature death of her husband Albert, Franz Joseph resolved to captain the ship to the very end, come hail or high water.

As it happened, there was plenty of hail and high water for Franz Joseph. The Emperor survived an assassination attempt by a Hungarian nationalist in 1853, and plenty of others would have had a go if they were given half the chance. Political shocks came aplenty, capped by the notorious Redl spy saga of 1913. Franz Joseph's family life was also no bed of roses. The Emperor's marriage to Elizabeth ( 'Sisi' of Bavaria), a lady considered to be the most beautiful woman in the world, proved an awkward match, and she couldn't get on with her new Habsburg in-laws. Her life came to a tragic end when she was stabbed by an Italian anarchist in 1898. The imperial couple's only son Rudolf was also bound for tragedy - killing himself at Mayerling in the throes of an ill-starred love affair. If that wasn't enough, the Emperor's brother Max was executed by Republicans in Mexico, whilst his second brother died of water poisoning following a trip to Egypt. Franz Joseph's surviving brother Ludwig Karl also got into scrapes, and had to be exiled from Vienna owing to his scandalous behaviour. The final, formidable blow came in 1914 when the heir apparent Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Serbian nationalists. The murder sparked the First World War, and with it, the collapse of the Habsburg Empire.

Above: A commemorative postcard from 1908 celebrating the 60 year jubilee of Emperor Franz Joseph

EARLY YEARS

Franz Joseph was born in 1830 at Schonbrunn Palace. He was the eldest son of Archduke Franz Karl Joseph. The young Habsburg was not initially destined for a throne, but fate intervened. Franz Joseph's uncle, Emperor Ferdinand, was a bit of a wandered soul, and his public appearances had to be carefully stage-managed. A good-natured fellow at heart, Ferdinand loved nothing more than to clamber into a wastepaper basket and roll around the palace. However, with the 'Springtime of Nations' rocking Europe in 1848, crisis was on the cards. When the revolution broke out in Vienna - the streets erupting in violence - the bewildered Emperor inquired of his subjects: "But are they allowed to do that...?"

With the Iron Chancellor Metternich fleeing Vienna, some highly placed nobleman tried to avert disaster by ringing the changes. Freedom of the press was promised, and Ferdinand was convinced to step down in favour of his nephew, the young Franz Joseph. The new Emperor was crowned in December 1848 - he was eighteen.

HIS APOSTOLIC MAJESTY

In spite of the words of promise from on high, the Emperor began his reign in a somewhat cautious manner. Indeed, he oversaw the crushing of the Hungarian revolt, a move that led to an attempt on his own life (the assassin's blade was thwarted by the Emperor's stiff collar, and the lucky fact that a patriotic butcher spotted the attack and leapt to restrain the assassin. The butcher was ennobled, and the assassin met with a rather more grim fate).

In 1857, the Emperor approved the demolition of the old city walls, paving the way for the grand Ringstrasse project. This huge endeavour was largely funded by the emerging bourgeousie. The rise to power of this group was partly aided by military failures, and amongst the consequences of a series of unsatisfactory wars was a compromise with Hungary: the 'Dual Monarchy' was born in 1867. The Emperor also approved autonomous concessions in Galicia, where the Poles took most of the reins of power after 1870.

With a new liberal constitution in place, the stage was also set for a revolution in the arts. The fin-de-siecle period became one of the most fertile eras in the history of the Habsburg monarchy, and although the Emperor's own tastes were decidedly conservative - he preferred hunting to the opera - he presided over an era of unparalleled artistic brilliance. Gustav Klimt and the Secession movement need no introduction, whilst in music, Gustav Mahler blazed a controversial trail.

As mentioned earlier, Franz Joseph's family life seemed to be a domino rally of disasters. His beautiful young wife 'Sisi' provoked scorn in some aristocratic circles for her vivaciousness, which was deemed unseemly for an Empress (comparisons with Diana Princess of Wales are not entirely lacking in substance). She also preferred Hungary to Austria - another factor that wound up Vienna's conservatives. Her only son Rudolf, who embarked on a doomed love affair, sparked one of the most dramatic scandals of the nineteenth century. To this day there is speculation as to who exactly killed who at the Mayerling Hunting Lodge (1889) - the family tried to hush up the details at first - but most surmise that Rudolf shot his seventeen year old lover and then turned the gun on himself, knowing that their relationship had been without hope. The Empress was herself murdered nine years later by an Italian anarchist.

As the tragedies mounted the Emperor remained steadfast in his duties, rising at 3.30am each day. He was technically available to every subject in his Empire, and he held twice weekly private audiences between other duties. One of his few consolations amidst all the earthquakes was his companionship with an actress, Katharina Schratt (who later refused to publish her memoirs in spite of being offered astronomical sums). The Empress Elizabeth, who spent most of her time abroad, had encouraged Franz Joseph's affair for many years, and it continued until the Emperor's death in 1916.

By the turn of the century, the redoubtable Emperor seemed an almost immortal figure. Yet unbeknownst to the Habsburgs, the Empire was on its last legs. The loyalties of the twenty-four subject nations ranged from the devoted to the darn right rebellious, but it was Franz Joseph who so often held the enterprise together.