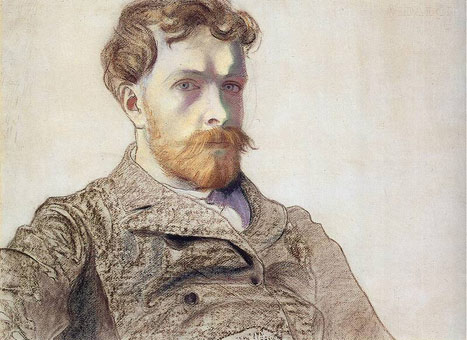

Stanislaw Wyspianski (1869-1907)

It would be nice to think that there were scores of talented artists on the verge of rediscovery. And perhaps it's true. For if anything can facilitate such a development, then it's the internet. Historians tracing obscure figures now have search engines, and at the click of a button, a crucial lead can be found, whether it's an Icelandic sculptor you're after or a dodgy sixties pop song on the verge of oblivion.

Poland, stuck behind the Iron Curtain for half a century, has plenty of figures that are ripe for rediscovery. Most hail from the era 1850-1950, and many achieved considerable international success in their day. Their names are by and large horribly unpronounceable to Western tongues, especially to chaps who've just drunk fifty beers on Cracow's Market Square. That said, most of Stanislaw Wyspianski's artist friends could give today's beer tourists a run for their money: a hundred years ago, the parties at Michalik's Cafe were the talk of the town, and a fair few poets came a cropper as a consequence.

Stanislaw Wyspianski (Staneeswaf Vispeeanskee ) did die young, but not from over-drinking. No, as memoirs recall, he tended to sit sketching quietly while his friends tucked into the liquor. Having studied in Cracow and Paris (where he was taken under the wing of Paul Gauguin, 1894), he was one of the first artists to be invited to join the Viennese Secession (1897). By then he only had ten years to live, but in the decade that followed he managed to pen Poland's best-loved play, create the country's most original church interior, and even knock off an epic plan to rebuild the Royal Castle Citadel (the latter unrealized). That might seem enough for one earthling, but grand as these three projects were, they barely scratch the surface of Wyspianski's career. Painter, poet, and play-wright, as well as a designer of stained-glass, furniture and stage sets, he was an 'uomo universale' in the Renaissance mold.

Above: Pastel self-portrait by Stanislaw Wyspianski (1903). The signs of illness seem already pronounced.(The portrait hangs in Cracow's Wyspianski Museum.)

Although there's an excellent museum in Cracow dedicated to Wyspianski, the best introduction can be found in the Franciscan Church. Several of Wyspianski's artistic projects were turned down elsewhere - his designs were frequently considered too daring - but here he got free reign. The church interior was in dire need of sprucing up as there had been a major fire in the vicinity in 1850. Wyspianski wasn't going to miss his chance, and on winning the competition he set about transforming the church according to his vision. Taking the Franciscan bond with nature as his cue, the artist covered the walls with a complex interplay of floral motifs. He also designed the famed stained-glass windows, jettisoning the medieval practice of using single panes to tell individual stories. The results tend to bowl over visitors to the church.

Allergic to oil paint, Wyspianski was obliged to seek other mediums in his portaits and landscapes. He settled on pastel, and his experiments with it were strikingly expressive. A decent selection can be savoured in Cracow's Wyspianski Museum, including portraits of his friends and family.

Wyspianski's achievements in the plastic arts were matched by his forays into the literary world. Author of several celebrated plays and poems, his masterpiece remains 'Wesele' (The Wedding). This play was hailed as a triumph when premiered at Cracow's Slowacki Theatre in 1901, and it has stayed in fashion ever since. 'The Wedding' centres on the awkward relationship between the intelligentsia and the peasantry, and the concomitant dream of national revival (at this time Poland was divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia). The intelligentsia believed that the peasantry - the last uncorrupted body of the nation - had to come on board if Poland was to be reborn. There was a frenzy for folk art, folk fashion and generally all things folkish. Several artists took the ultimate step by marrying a comely peasant girl - Wyspianski did so himself - and 'The Wedding' is based on just such a union, that of poet Lucjan Rydel with Jadwiga Mikolajczyk. Wyspianski attended Rydel's wedding at his friend's house in the country. Apparently Wyspianski didn't say much, but afterwards he wrote the play directly based on the experience. During the drama, noblemen, men of letters and country folk dance... Phantoms from Poland's past emerge - kings, seers and soldiers - taunting the Poles and admonishing them to seize the initiative. The best introduction to the play remains Andrzej Wajda's film version, which is today readily available on DVD (English subtitles). And one of the measures of Wyspianski's success is that some of his literary phrases have entered into everyday speech, much like Shakespeare in English-speaking countries.

Of course, not everything Wyspianski touched turned to gold, and Cracovians often complained that his furniture was unbearably uncomfortable. This was the case with the seat of the Society of Physicians, where he also designed an extraordinarily original stairwell using chestnut leaf motifs. However, Wyspianski's common reply was that the chairs were not supposed to be comfortable, as otherwise visitors would go to sleep.

The last years of Wyspianski's life were made pitiable by illness (it is accepted that he contracted the French disease as a student in Paris). He continued to work - he was made professor of painting in 1896 - but he was not at all well. When he passed away in November 1907, the nation mourned. He was laid to rest in the small Crypt of Honour beneath Cracow's Church on the Rock, where today one can find his tomb alongside Karol Szymanowski and Czeslaw Milosz.

Comments

I have just returned from a short break in Krakow and was full of admiration for the unusual wall-paintings and windows in the church of St. Francis. I had never previously heard of Wyspianski, and next day went to the museum dedicated to his work. It was fascinating to see the enormous variety of his talents. A visit not to be missed!

ReplyI first saw a painting by Stanislaw Wyspianski in a hotel room in Zakopane. Since then I have purchased two prints which I proudly framed and are in my home. My visitors admire them and I have been to his museum in Krakow. One of his paintings is of Helena 1905 and reminds me very much of my daughter although 1905 is the year my mother was born, is this telling me something? I love his paintings and was in Krakow in 1907 when a big dispay in the park. Thank you

ReplyNice to see a contemporary review of the artist instead of a history lecture! Only one small negative comment, and that is that his date of death is wrong (1907 wasen't it?).

Reply